INTERVIEW WITH AMBER ZORA

Amber Zora is an interdisciplinary artist based in Rapid City, SD. She received her Bachelor of Arts degree from University of Alabama at Birmingham and a Master of Fine Arts degree in Photography + Integrated Media from Ohio University. She was enlisted in the US Army for 8 years and deployed to Qayyarah West, Iraq as an ammunition specialist from 2006-2007 with the 592nd Ordnance Company.

How long would you say you’ve been creating art (in any medium, since you practice in many)?

I asked my parents for a camera in 2001, when I was in high school. They purchased a 35mm Minolta Maxxum 5 with a 28-80mm lens for my birthday. I took photographs of friends and what I felt was artsy. I still have this camera and brought it on my 2023 residency to the Arctic circle.

entrenched exhibit entrance featuring Amber Zora (Hoy)

How did you end up joining the military? And how did you bring art with you?

After high school, I went to college for a year to study art education because I couldn’t really imagine what other careers were out there for artists. I thought maybe one day I would be a K-12 art teacher. I grew up in a rural area; I did not have access to viewing contemporary art in a gallery or a real understanding about what jobs were available in the art field. I didn’t know anyone who was an artist. It’s interesting because now I actually contract with public schools to teach watercolor courses.

I joined the military the summer after my first year of school because I was worried about student loan debt. But joining the military in 2005 put going to school on hold for a while; I deployed to Iraq in 2006-2007. I didn’t make work explicitly about the military while in the service. I needed a pause between my service and creating work about it—time to process and reflect on what happened.

Before the military, I created work that other young art students often create: I drew copies of master’s studies or pop culture references and took moody photos. While in the military, I would sketch in a journal whatever was around me, like my boots, a landscape, or a crumpled up water bottle. Sketching helped me feel a bit less lonely during deployment. Sketching was also an easy medium to take on the go. And I always had a camera on me, but I didn’t consider these exercises artistic work. I was simply taking photos with friends who were also in the military or documenting us at our job. Later, some of these works would find their way into my thesis exhibition, entrenched.

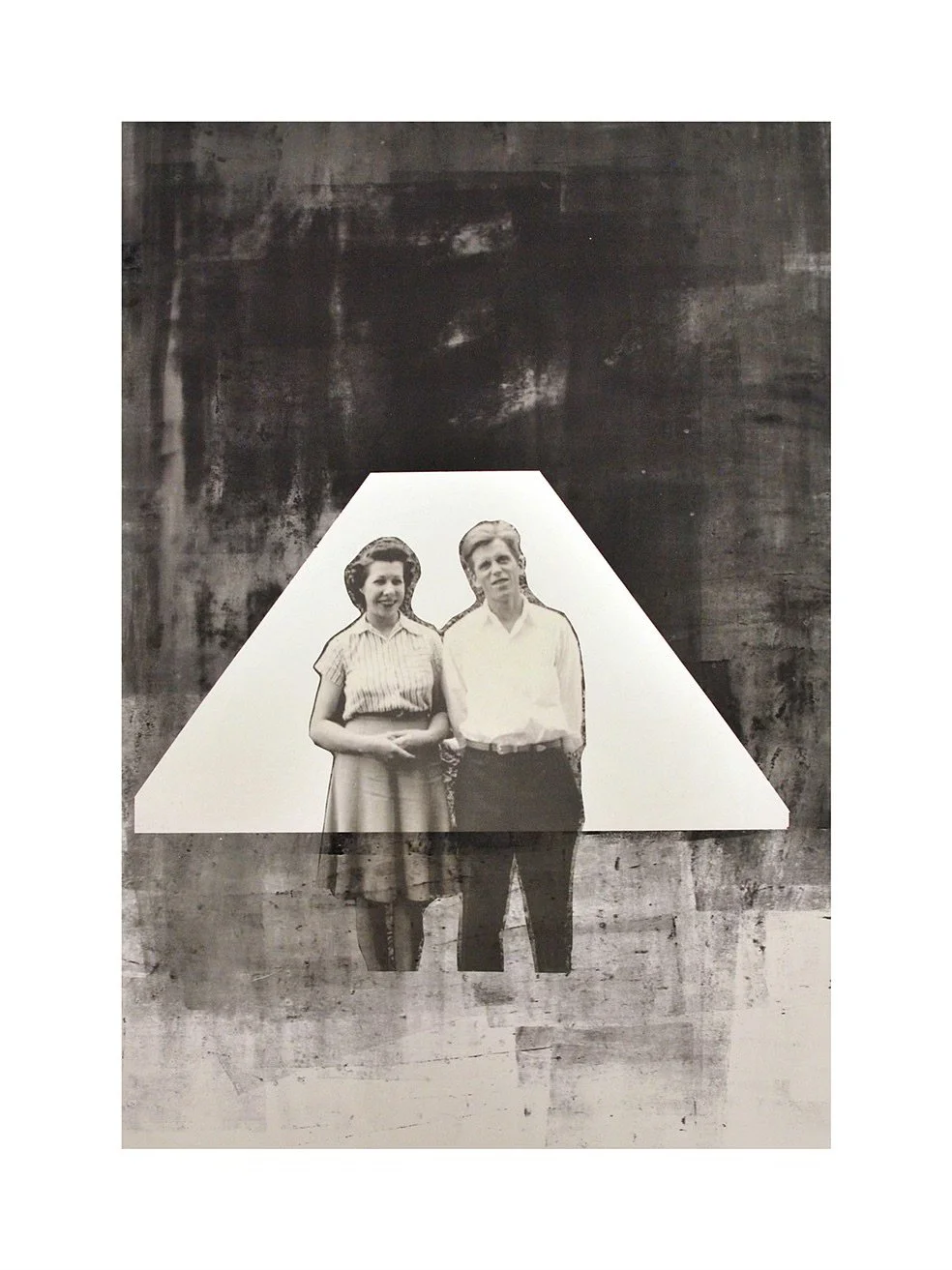

from entrenched

It wasn’t until after my deployment that I knew I would only spend time on something I truly loved or cared about. I went back to school, and even though I floundered on what degree I wanted to pursue and switched colleges a few times, I ended up focusing on (and earning) a BA in studio art from the University of Alabama in Birmingham in 2012. None of this represented a direct path, of course, but I then decided I wanted to get an MFA to continue with fine art.

“I grew up in a rural area; I did not have access to viewing contemporary art in a gallery or a real understanding about what jobs were available in the art field. I didn’t know anyone who was an artist.”

What did your 2006-2007 deployment cost in terms of your art and ability to create? What did it leave you with?

One of my high school friends died from an IED explosion, and the Global Warrior on Terror has left me in a state of perpetual ennui. Sure, my deployment may have given me some kind of global perspective that has shed light on issues I maybe wouldn’t have approached as a civilian, but it’s taken far more light away from my world.

I was 20 years old when I was deployed and hadn’t really built an art practice yet, or style. There’s not much to compare my art practice to, in terms of how my deployment disrupted my work. But my deployment did give me a perspective shift. After I came back and grounded myself, I knew I couldn’t just do any kind of work; life is short and I wanted to spend the rest of the time I had on this earth doing something I could get behind. I wanted to push that practice as far as I could. So I went to undergrad and graduate school for art. If it wasn’t for the GI Bill, I would not have considered going to grad school.

Plus, after becoming involved with other like-minded veteran artists, I realized that I wasn’t alone in my thoughts about the military, and around peace and justice. My veteran art community has really helped me stay active in continuing to make work.

“Sure, my deployment may have given me some kind of global perspective that has shed light on issues I maybe wouldn’t have approached as a civilian, but it’s taken far more light away from my world. ”

How did you find your veteran art community?

I took a few chances to find a veteran community. I heard about a papermaking class being offered by veterans a distance away from where I was living. I wanted to learn that craft, so I drove 5 hours away and got an Airbnb for a week to learn and meet people. To someone trying to find their veteran community, I would say: start locally, and if that community is not there, look at ways you can be connected nationally.

Do you create in multiple mediums simultaneously, or do you tend to focus on one at a time?

Currently, I’ve been working in monotype, photography, and watercolor. I work simultaneously in these three mediums.

Photography will always be my first love; film photography is magical. I remember learning darkroom photography and being totally in love with the process of seeing images emerge. In the entrenched series, I use film and digital images. Some images in this series are from disposable cameras that I had during training or deployment, some are from digital shoots (which were pretty limiting in the early days of digital), and some photographs were taken during grad school while responding to my stories and time in the service. I presented [those] images with audio stories as well.

I’ve been using monotype for the series Welcome to Rocketown, about the pyramid of North Dakota. Three of these pyramids were to be built in the U.S. but only one was built before the program dissolved. Monotype seemed appropriate. My great grandfather worked at the pyramid and painted the inside of missile sites in North Dakota. So this work and other works have been about my family’s dependence on the military economy.

And, because so much is screen-based (photo editing, updating websites, even checking/writing emails) I got into watercolor to have an artistic medium that was a bit more tactile and something I could carry with me.

In your experience, what role does rural America’s dependence on the military economy play in the United States’ artistic history? And in women’s history? I see the work in entrenched and Shelterbelt as a kind of visual response to this question, but I wondered what your words would be.

from Shelterbelt

I would say that rural America has been left out of US artistic histories in general, as well as nonbinary people and women. Non-cis men are also left out of a lot of histories (in general, around the world). National funding earmarked for cultural and artistic programs often doesn’t make it to rural areas, where people are focused on the bread and not the roses, if you are familiar with the “Bread and Roses” slogan.

U.S. nationalism and militarism is delivered to [rural areas] through Hollywood and other media; it’s a huge industry that is sewn into our everyday lives that we honestly do not see until we do, then it’s everywhere. It’s humming right along at sporting events, holiday commercials, military-sponsored video games. The military is relying on these messages to recruit people from all walks of life, but especially rural America. It’s a kind of feedback loop.

Veteran artists are generally pushing back against the status quo of the above described campaign.

The stories you’ve recorded left me dumbstruck, particularly the final lines of a couple (“Trays” and “Stool”, for two examples). Are these meant to be connected to particular pieces in entrenched?

When I created entrenched, the intention was to provide audio stories in conjunction with the photographs and allow for slippage between the audio and the images—to let the viewer build connections on their own. (For instance, I imagine the viewer hearing one of the stories that involves a red car [“shoes”] and connecting that story to a close up photograph of a dented red car.)

However, there are photographs that are not explained in the audio and audio stories with no related image [i.e. “Stool”]. My hope is that the viewer understands that the stories and images contain poetic relationships and that the work is both revealing and withholding clues. The viewer is bringing their own interpretation to both the stories and photographs. I imagine the viewer on a journey with me.

For this particular project, I thought a lot about the target audience member being a 20 year old woman in the military. My deployment was a pretty lonely experience and there were a lot of things I did not know how to navigate. There were only four women in my unit, and when we deployed, we were all lower enlisted, so there wasn’t a female leader to help advocate for us and to let us know what was okay (“this is just what war is”) and what was not okay.

“There wasn’t a female leader to help advocate for us and to let us know what was okay (“this is just what war is”) and what was not okay. ”

Could you talk about the relationship between sexism within the military and beyond it? (This is a sort of nebulous question, I know; I’m thinking, in particular, of all the times I’ve been told lately that “the army is changing,” as in sexism is no longer a problem.)

I’m skeptical of the notion that sexism has been fixed in the military because there is sexism in our culture. How would that even be possible? In any male-dominated field where machismo is the norm and rewarded, you are going to find more sexism. There are the same problems in the military that exist in civilian workplaces, but they tend to be magnified [in the military].

Is it possible that sexism in the military in some ways may be getting better? Maybe, but compared to what? Vanessa Guillén was murdered on Ft. Hood by another soldier in 2020. Before her murder, she expressed not feeling comfortable or safe on base, but nothing changed, and she is one of many who spoke up. This is a very real issue that still needs to be dealt with.

Almost every woman I’ve served with has experienced some kind of military sexual trauma or sexual harassment. My military experiences included inappropriate comments, jokes, attention and touch. That kind of dehumanization can whittle you down over time. I believe my gender also affected my promotions, and I had to work harder to prove that I was capable of doing my job. Everyone’s experiences in the military are so different.

“Almost every woman I’ve served with has experienced some kind of military sexual trauma or sexual harassment.”

What do you do when your practice gets stuck or stalled?

from Cold Coast

After I completed entrenched, I felt a bit stuck with my photo practice. I had told all the “big” stories of my military journey, and I didn’t know if I wanted to keep making work about the military.

That was about the time I started doing ink drawings about the Cold War and became interested in my role as an ammunition specialist. (Also side note: I realized my experiences in this world go beyond the 8 years I was in the military. [I didn’t want] to be constantly looking to the past but looking forward as well, to a future in work that isn’t so depressing. Curating and working on group projects is helpful to combat these moments of feeling that I really don’t want to be the center of my work anymore.)

Can you tell us more about your Cold Coast series?

from Cold Coast

The Cold War work is what sent me to the Arctic circle for the Cold Coast series. The Arctic was an area of interest during the Cold War because it was thought that, if the USSR was going to send bombs, they would go over the arctic circle. This is why the DEW line (Distant Early Warning system) is in Canada. Currently, the Arctic is a DEW system for climate change, and the U.S. military is the largest user of fossil fuels and energy in the US government.

The series is of two separate spaces: the Pyramid of North Dakota, and Svalbard, Norway. I’m actually going back to the Arctic [in 2024]. I feel like I’m still at the beginning of the Cold Coast project. I started taking images at the Pyramid because my great grandfather worked there as a civilian; as I mentioned earlier, he painted the inside of missile silos in North Dakota as a general laborer and he was really proud to have the job. The more I looked into the Pyramid, the more interested I became in the military’s impact on the town and neighboring farms from an economic and environmental standpoint.

“...to be in communion with glaciers, I would sway between the utter sadness of how humans are allowing this to happen to the planet, how the U.S. military is this huge contributor to climate change, and my smallness in front of such old ice and the landscape. ”

from Cold Coast

The town was excited to have this new industry that would bring in jobs and opportunity. From my perspective, though, the military came in, used it up, and left. The facility was not open very long. Some people say it was only fully operational for a day, some say a few months, some people look at the building and development of the cluster of facilities around Langdon as a part of the bigger project. There is a whole groundwater incident I won’t go into, but the Department of Health had to step in.

When I went to Svalbard, I was thinking about the Pyramid, the DEW Line, and watching the Arctic sky—how these secluded areas that one would not necessarily associate with war are still touched by militarism. Svalbard is a demilitarized zone, but during WWII, Nazis had weather stations there. This also led me to questions around demilitarized land: is land inherently militarized if it is not deemed demilitarized?

It wasn’t until I was in the Arctic that I started to think about how the Arctic itself is functioning as a DEW system for climate change, as it was a warning system during the Cold War. When you are in such a remote place thinking about an apocalypse, you can kind of imagine the apocalypse has already happened. And to be in communion with glaciers, I would sway between the utter sadness of how humans are allowing this to happen to the planet, how the U.S. military is this huge contributor to climate change, and my smallness in front of such old ice and the landscape. How can the Arctic be so brutal, beautiful, and fragile at the same time? I’m not sure if I can sum the feeling up about how the massive landscape has a psychological effect; [you] walk for miles and miles and seem to not move at all. And that the brutality of the place, like most of nature, feels somewhat impersonal.

There’s a point in your initial responses when you touch on the idea of not wanting to be the center of your art anymore. How does one maneuver through/around/away from her art?

My art will always be about my experiences in this world and the people around me. What are we if not a mix of all the information we are constantly taking in?

After my thesis exhibition, which included military photos, civilian photos, and self portraits, alongside my audio stories, I thought, “Well that’s it, those are all the best stories and the best photographs. Now what do I make work about?” and I also thought, “Do I have to make work about myself or the military forever?”

It’s important to remember that we all contain multitudes and have interests outside of ourselves. I get a lot of ideas about new work to create from reading nonfiction and looking at the work of political artists and veteran artists from the past and present.

“It’s important to remember that we all contain multitudes and have interests outside of ourselves.”

What are you reading?

The last couple years I’ve read books that are part of the anti-war canon, like Kurt Vonnegut and Tim O’Brien–the common titles that I somehow missed in high school. Right now I’m reading a George Saunders book, Lincoln in the Bardo. I also love Rebecca Solnit’s work, and science fiction. When I’m reading for leisure, I’m attracted to literature that poses complex questions about the world we live in but also leaves room for some suspension from reality and humor.

I read books and catalogs as a part of my studio practice as well. Some of the books include artists’ responses to the war, like Kill for Peace by Matthew Israel, A Different War by Lucy Lippard and the MoMA PS1 Theater of Operations catalog.

cover of Ginger featuring an image from entrenched

You also mention being comfortable with the descriptor of “veteran artist” but unsure about seeing your work limited to military-connected projects and exhibitions. We’ve noticed this limitation too, especially as it affects veteran artists; they are often siloed within the wider artistic community as an isolated collective the general public can choose (or choose not) to engage. I wondered if you could talk more about that.

Knowing an artist is a veteran when looking at their work allows the audience to locate and contextualize the artist and their experiences historically. In that sense, the label of being a veteran artist is pertinent, particularly if the artist is making work about global conflict.

From my experience, however, sometimes audience members and media become more interested in the veteran artist’s narrative and personal story than the themes within the work presented, and in that case, the veteran title can be distracting. You can imagine, as an artist, if you want to have a discussion about your work [beyond military service] and the conversation keeps turning back toward that singular identity, themes you are not presenting and parts of yourself you didn’t plan on sharing, that it could become frustrating.

Also, veteran artists are often asked to talk about their healing publicly, which I think is inappropriate. Veterans can provide perspectives that need to be shared with the public to gain understanding about wars and US conflict; we’ve seen this activism and truth telling play out in the Winter Soldier Investigation of 1971 with Vietnam veterans sharing their experiences and the Winter Soldier: Iraq & Afghanistan in 2008. But veterans tend to be [seen only] within the healing arts—and I don’t want to knock that because it’s important for veterans to get what they need—but when you look at an artist as a person to be studied—and their practice as a healing journey—you tend to lose focus on the fact that they are making artwork at all.

“I’m okay with being called a ‘veteran artist’, but am I okay with only being in veteran exhibitions? It prompts the question: do people connect with my work, or are they including me to complete a grant that ‘serves veterans’?”

from Shelterbelt

Within the veteran art field there are the healing arts, the MFA artists, the self-taught who have a serious practice, the political, the non-political, etc. And within these categories, the works are not doing the same thing. I keep seeing veterans thrown into a show together because they share the single experience of being a veteran. I think this is lazy curation, and it silos or typecasts artists that could occupy other arenas. I would urge curators to think about the goals of their veteran exhibition and the other ways artists are tied together. (I’m okay with being called a “veteran artist”, but am I okay with only being in veteran exhibitions? It prompts the question: do people connect with my work, or are they including me to complete a grant that “serves veterans”?)

Veterans are also not the only ones that experience war. Combatants and civilians on the ground have the most direct bodily experiences with war, but military family members also experience the pain of not having their loved ones around and the possibility of them never returning. War is not a singular experience.

We’ve read a couple bios/articles online that feature you and your work; from that, we know that you’ve taught throughout the pandemic. Are you currently teaching, and if so, where?

During the pandemic, I taught a few one-off classes online through Frontline Paper, Warrior Writers and the Wisconsin Veteran Museum. I work for the DEMIL Art Fund and teach through the South Dakota Art Councils Artists in Schools & Communities program. These are generally one- or two- week gigs teaching in public schools, after school programs, or community centers. I’ve taken on contracts from nonprofits to curate exhibitions or help with programming since leaving full time salary work. And the Surviving the Long Wars program in Chicago was a huge event/exhibition/program.

What are you working on now, and what do you have planned?

from Shelterbelt

I’m still working on the photo series Shelterbelt. I feel like it might be Part II to the entrenched series. I was in North Dakota reading a family history document that my grandmother had written out, and there was a lot within this account about my maternal history and what women in my family endured to either keep their independence & freedom…and if [those] were not available to them, how they kept their families together the best they could or stole moments for themselves. (It also wasn’t lost on me that, as I was reading this document, several of my female friends were making really tough decisions for themselves and their families around safety and security.)

The area in North Dakota that my family is from is incredibly rural and isolating, so many of them had to look inward for solutions to problems. Some moments included my grandmother patching holes in the walls with ripped up sheets and wheat paste, swapping homes with another family to get away from an abusive second husband, and one surprising bit (because my family is so religious) is my great grandmother having friends over to read their cups/futures.

At the end of August 2023, I went to Frontline Paper in New Jersey to do a week-long printmaking residency and to expand on my Welcome to Rocketown series. And I’m doing work that addresses women, the military, [the question] ‘what is life after military service when you are a woman?’, and the quietness of returning home & creating a home.

For now, I’m at Monson Arts in Maine, working on images around the Arctic, North Dakota, and moments that feel a bit cataclysmic. I suppose this work is kind of like what I was talking about when I mentioned not making work specifically about myself. It’s informed by my experiences as an ammunition specialist and the questions I have, like how many bombs are enough? How much military is the right amount?

watercolor of mushroom cloud cake cutting

I’ve been thinking about this mushroom cloud cake and have been revisiting the image a lot. It’s a celebration of successful weapons testing during Operation Crossroads at Bikini Atoll. The cake image is eerie and bureaucratic. With this image, I think about the people who make decisions to build these programs and the service members that realize them, then the people and environments that are harmed. I’m making work about the Cold War and obsolete weapon systems because I think it is easier for me and audience members to see the absurdity in it, like consuming scifi. In my mind there is a direct link between the arms race to the inflated military budgets we have today.

My hope is that if we can see the absurdity in the past, we can question the absurdity of the present.