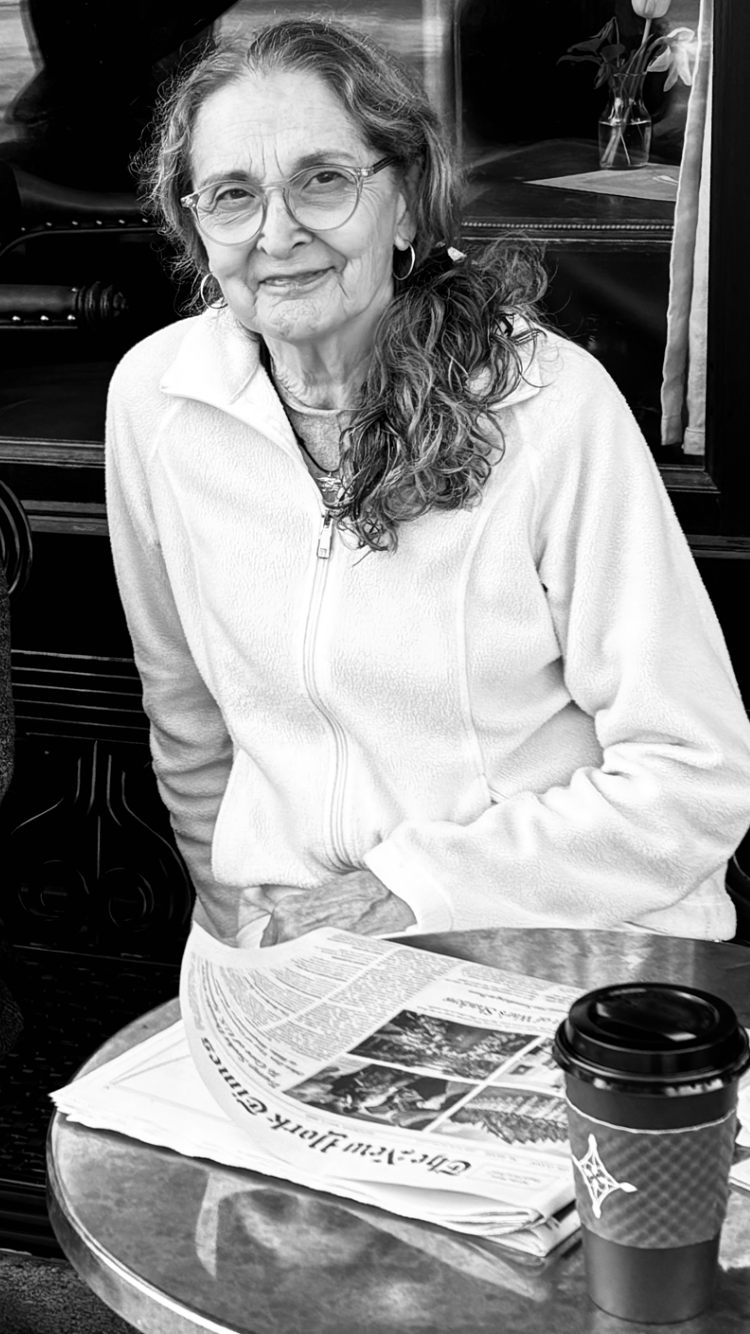

Julie Friar

Shrapnel

The scent of evergreen resin fills early-March air in the cultivated forests of Germany’s western Ardennes. The forest floor is freshened to soft chartreuse by the lingering edge of a low cloud. Unfurling fiddleheads poke through the newest sprouts of moss, our steps muffled as my husband Jack, our guide Karl, and I tramp through the light mist. Off to the left, spruce boughs litter a swath of ground, detritus pruned from newly harvested trees arrayed in orderly rows. Their black bark is in contrast to the saturated greens of the overstory. An arriving spring will imminently obscure the features we’re here to find in this landscape. Karl points, says: “That mess over there, the broken branches, splinters, knots of wood create an impression of how it might have looked after an overhead explosion. German artillery were timed to detonate in the treetops to create a bigger effect on the ground from falling limbs and debris.”

We are standing on hallowed ground, a few miles east of St. Vith, Belgium. You wouldn’t know it. There are no monuments, markers, flagpoles, or informational posters, no visitor’s center or museum, no tourists. It’s a section of what was the Allied front line in December 1944: then a foggy, frozen, elevated outpost above a windswept rock formation known as Schnee Eifel. The 106th infantry division traveled through Belgium to this spot in Germany and occupied it on December 10, 1944. My father, Pfc. Calvin Friar, was among the soldiers positioned here.

Today, eighty years later, we are looking at a schematic diagram of where the division was positioned on this ridge. Hand-drawn on translucent paper and dated “15 Dec 1944,” symbols were employed to locate command posts (rectangle with an ‘x’), platoons (semicircle with three dots), or squads (semicircle with one dot). It was to be delivered to division headquarters in St. Vith and overlaid on a topographical map. Six C company squads (about 90 men) were scattered in front of a command post bunker. Cal was there, located in one of the semicircles with a single dot. One such symbol represents 15 soldiers. Cal Friar is 6.5 percent of one such symbol.

The division arrived on December 10 to replace troops who had been there since September. The December 15 diagram communicated important information but was soon irrelevant. At dawn on the 16th, Hitler’s generals launched a surprise counteroffensive to break through and encircle those positions, intending to proceed to St. Vith, Belgium, and from there to Antwerp, capturing fuel, equipment, and munitions along the way. He ordered his generals to make this happen in a single 24-hour timeframe. I would like to write: “the rest is history” but history has not so far written the full story. And, as it is typically told, misrepresents important parts of the story.

On December 17th, Cal’s battalion commander was killed. Circumstances on the Schnee Eifel became so dire that the encamped regiments were ordered to withdraw. In his journal account, Cal wrote: “On the 18th we were ordered to pull out and attack.” On the 18th. Three days after initiating the counteroffensive, Hitler’s generals, faced with stiff resistance from the units of the 106th, were bogged down in the area outside St. Vith, necessitating a revision to the plan: the German counterattack had to shift direction. Determined to arrive in Antwerp, they would go around. Hitler set his sights on Bastogne.

Wisps of fog hang in the trees, like vapors from returning souls seeking peace. They are cool on exposed skin as we tramp amongst softly contoured remnants of foxholes, z-shaped slit trenches, and shallow foundations of low-built log structures used as machine gun emplacements. These were dug to protect the command post, now a curiously out-of-place hill of dirt covered in tangled dead branches, rotting logs, naked saplings, and leafy debris: the concrete bunker, originally constructed by the Reich and occupied finally by Allied troops, was destroyed and buried by French engineers after the war.

I’m standing slightly behind Karl’s right shoulder, peering at the schematic and following his gestures, listening intently while he softly tells tales of the 106th. Jack and I follow along as he moves around the area of the bunker looking at the map, glancing up, looking at the map, glancing in a different direction when he sees something on the ground and reaches down. “What’s this?” It’s heavy, a rusted bit of curved jagged metal the size of a salad plate that’s pitted, pebbly, and shedding oxidized iron in flakes. “I’ll tell you what I think,” he continues, “I believe this is shrapnel, a piece of exploded shell casing…” The shallow saucer-shape had striations on one tip, perhaps threads to be attached to something. About one quarter inch thick, it is heavy to hold, too big for a pocket. One can imagine that, years ago, these edges and points were razor sharp.

Taking it from him, I experience the sense of dislocation that arrives with sudden insight. I wonder about the moment this shell exploded in the air above the infantrymen, whether it achieved its original lethal intent as the blast hurled metal shards in all directions. Cal Friar occupied a foxhole indicated on the diagram and, with his combat team, certainly experienced this munition’s effect. Here is a lingering leftover, this shrapnel with its attached traces, at rest among dug-out remains occupied decades earlier. But the wreckage of those moments is not so apparent now. It requires a guide like Karl to interpret the scene, to have the schematic, to have developed a sixth sense that recognizes a bit of debris and its significance.

Standing in this forest in proximity to the bunker and its defending positions, looking at the diagram and holding the shell fragment, a whiff of knowing the unknowable permeates the air. Cal and many like him wouldn’t talk about the war, determined not to be an object of anyone’s projections. But his generation has passed away, leaving subsequent generations in the dark about the price of liberty. Inadvertently, they delegated the narrative to others. If history is written via the stories of the individuals who lived it, then I intend to communicate the thing they believed was better left unsaid.

“Can I keep it?” I ask Karl, holding the heavy rusty remnant with both hands, close to my heart.

“I’m inspired to inform myself about aspects of wartime experience affecting the Greatest Generation and the democracies they were defending. In the fighting my essay describes, my father was wounded, then taken prisoner. He was ‘lucky:’ when Hitler surrendered, he could return home and marry my mother. He refused to speak about his experience, but left a trunk of circa 1944-45 letters and papers to be discovered later. So, I have a sense of his life then. I want to understand how combat experiences impacted his ‘normal’ life, our family’s functioning in the face of The Secret About What Happened, and to infer the emotional process and ingenuity that brought him back safely.” —Julie Friar

Julie Friar first worked as a technical writer in the financial sector, then as a stringer for a financial trade journal. She experienced a call to healing arts that propelled her second career as a licensed physiotherapist in private practice, where she focuses on pain relief via therapeutic massage and yoga-based therapeutic exercise. She researches and writes about family members who are veterans of wars fought in and by this country, with the hope that coming generations will appreciate that they have a personal stake in what was required to preserve the liberty we enjoy today. She holds M.S., Admin & Supervision (U of Hartford), and Doctor of Physical Therapy (Marymount University).